I came across this Charles Bukowski poem for the first time last week. As the man says, it's a beauty.

The Laughing Heart

your life is your life

don’t let it be clubbed into dank submission.

be on the watch.

there are ways out.

there is a light somewhere.

it may not be much light but

it beats the darkness.

be on the watch.

the gods will offer you chances.

know them.

take them.

you can’t beat death but

you can beat death in life, sometimes.

and the more often you learn to do it,

the more light there will be.

your life is your life.

know it while you have it.

you are marvelous

the gods wait to delight

in you.

Sunday, March 25, 2007

Monday, March 12, 2007

Charles Einstein 1926-2007

Charlie Einstein was a pro.

A veteran newsman, novelist, sportswriter and television scribe, Charlie was one of a kind. I got to know him well over the last six or so years, while serving as his editor at The Newark Star-Ledger. For as long as anyone could remember, Charlie had been writing an Atlantic City entertainment column for the paper, and was still doing it well into his late-70s. I inherited the editorship of the column in 2000, and thus began a series of weekly phone conversations with Charlie about his column, books, movies and life in general, generally punctuated with his trademark “Stop me if you’ve heard this one ...” jokes.

To me, at first, he was just the gravel-voiced, old-school columnist who turned in a short piece each week in a style that was more akin to Ed Sullivan’s “Talk of the Town” than anything that had actually appeared in a newspaper after 1950. Often our exchanges included comments along the lines of “Uh, Charlie, I think we should change this reference. I don’t know if many people these days know who Yogi Yorgesson is.”

But gradually over the course of those phone calls – a little bit at a time, often through oblique allusions – I started to pick up on some of Charlie’s amazing history. His father was Harry Einstein, a radio, vaudeville and film comedian who billed himself as “Parkyakarkus” and was a regular on Eddie Cantor’s NBC broadcast (he also became posthumously famous for suffering a fatal heart attack at a Friar’s Club roast in 1958, when tablemate Milton Berle’s cries of “Is there a doctor in the house?” were misconstrued as shtick).

Charlie had two half-brothers as well, from his father’s second marriage – Albert Einstein and Bob Einstein. Albert, of course, eventually became writer/director/comedian Albert Brooks, and Bob went on to cable fame as “Super Dave Osborne” and is now a regular on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

Charlie would never volunteer any of this though. You had to come to those conversations already armed with background information, or the references would fly right past you. Born in Boston, Charlie attended the University of Chicago shortly after the Manhattan Project produced the first nuclear chain reaction in an underground laboratory beneath one of the school’s athletic fields (“We used to joke that our locker room was the nicest in the country,” he’d say. “But the water in the showers was radioactive.”)

In Chicago, Charlie started working for International News Service, which would eventually become part of UPI. While there he wrote his first novel, THE BLOODY SPUR, a newspaper drama/serial murderer thriller based on the crimes of “Lipstick Killer” William George Heirens, a University of Chicago student whose murder spree terrorized the city in 1945-46. The book was published as a paperback original by Dell in 1953 and the film rights were bought by Fritz Lang, who turned it into his 1956 movie WHILE THE CITY SLEEPS, starring Dana Andrews and Ida Lupino (“The producers tried to sue Andrews because he was drunk on the set all the time,” Charlie once told me. “Which is funny because he was supposed to be playing an alcoholic in the film.”)

More books followed, as well as dozens of stories for magazines such as MANHUNT and SATURN, as well as “slicks” such as HARPER’S and THE SATURDAY EVENING POST.

But sportswriting grew to be his true love. After moving to San Francisco in the late ‘50s to work for the Examiner, he began covering the Giants and became friends with Willie Mays, a friendship that would last the rest of Charlie’s life. He co-authored Mays’ memoir “My Life in and Out of Baseball," and was the author of the oft-reprinted "Willie’s Time: Baseball’s Golden Age.” In the ‘60s, Charlie appeared in a pair of TV documentaries about Mays that were collected and updated in the recent video “Willie Mays: Born to Play Ball.”

But sportswriting grew to be his true love. After moving to San Francisco in the late ‘50s to work for the Examiner, he began covering the Giants and became friends with Willie Mays, a friendship that would last the rest of Charlie’s life. He co-authored Mays’ memoir “My Life in and Out of Baseball," and was the author of the oft-reprinted "Willie’s Time: Baseball’s Golden Age.” In the ‘60s, Charlie appeared in a pair of TV documentaries about Mays that were collected and updated in the recent video “Willie Mays: Born to Play Ball.”

Charlie soon became a major figure among sportswriters, and edited four volumes of the classic "Fireside Book of Baseball" series. But he continued to write fiction as well, including, in 1967, a science fiction novel for Fawcett’s landmark Gold Medal line, THE DAY NEW YORK WENT DRY, about a drought-plagued Manhattan collapsing into chaos. His editor there was an old friend, the legendary Knox Burger, whom Charlie had written for at various publications and publishing houses since the end of World War II. More than fifty years later, Burger would become my first agent. (“I always hated that title,” Charlie told me in 2001. ”My title was ‘The Day New York RAN Dry.’ Knox changed it to ‘The Day New York WENT Dry.’ Made it sound like it was about Prohibition or something.”)

Charlie soldiered on, writing a baseball column for the San Francisco Chronicle in the 1970s, and continuing to turn out novels and nonfiction works (he wrote one of the earliest TV tie-ins as well, a 1959 paperback adapting stories from television’s NAKED CITY). His 1978 novel THE BLACKJACK HIJACK became a TV movie titled NOWHERE TO RUN, starring David Janssen and Stefanie Powers. He also wrote scripts for LOU GRANT, to date one of the most accurate recreations of life in an actual metropolitan newsroom.

In semiretirement, Charlie returned to where he started, the news business. After relocating to New Jersey, he began writing that Atlantic City column for The Star-Ledger, a gig he held for nearly 20 years. The news content of the columns was minimal, the style anachronistic, but I soon discovered there was no sense in trying to alter Charlie’s voice. It was unique.

But in the last two years, he was fading and he knew it. Living alone outside Atlantic City (Corrine, his wife of 42 years, had died in 1989), he was often plagued by memory issues, his copy riddled with typos. He wasn’t ready to hang it up yet though. At the age of 75, with the aid of his sons, he bought a computer and learned how to use it, so that he could file his column electronically (for the two decades previous, he’d mailed them in, typewritten). I spent many afternoons on the phone with him, talking him through technical glitches (“I hit SEND and it says it’s sending but it’s not going anywhere!”)

But mostly I think Charlie just wanted to talk, especially to someone who knew something of his past, of who he’d been before, what he’d done. I sent him a signed copy of my first novel, THE BARBED-WIRE KISS, when it came out in 2003. In return, he autographed a first edition paperback of THE BLOODY SPUR for me. “To Wally, best among editors,” he wrote in it. “Where were you when I needed you?”

In early 2006, I got a very terse e-mail from Charlie, that was CC’d to others who knew him. He was leaving New Jersey, he wrote, at the urging of his son Mike, who wanted to bring him back to live near he and his family in Michigan City, Indiana (the picture at top, taken last April, is Charlie and his granddaughter Cayla). At first, Charlie hoped to continue the column, but that soon proved impossible. He called me a month later, after settling into his apartment at an assisted living facility. “This is a great place,” he told me. “I’ve got a nice room, a TV, my computer. But I’m locked in!” Still, he said, he was enjoying the slower pace and was catching up on his reading, including my second novel, THE HEARTBREAK LOUNGE, which I’d sent him with the inscription “Here’s my Gold Medal book ... 30 years too late.” More importantly, he told me, he’d started another novel himself.

In March 2006, I got another e-mail from him. “Wally,” it read. “One of the few pleasures of dementia is that of saving the best for last, and by last I mean writing to you. As excuses for not writing sooner go, that must rank right up there with Custer’s order not to take any prisoners, but it did give me the chance to re-read THE HEARTBREAK LOUNGE ... and where in my inscribed copy you apologize for being too late for Gold Medal, know that you weren’t too late. You just skipped the grade.

All Bests,

Charlie”

On Thursday afternoon, I came out of a story meeting to find a voicemail message waiting for me from Charlie’s other son, Jeff, Cayla's dad, telling me that his father had passed away the day before. It was followed by an e-mail from Mike. “I am sad to report that Charlie passed away yesterday afternoon at St. Anthony's Memorial Hospital in Michigan City,” it read. “His health had been steadily declining over the past year, culminating this week in the onset of pneumonia. He was admitted to the hospital yesterday morning and quickly slipped into unconsciousness from which he did not emerge. He was simply too weak to fight back any longer. He died peacefully in his sleep."

Peter Genovese wrote a fine obituary of Charlie (with comment from Willie Mays) which ran in Saturday’s Star-Ledger. It can be found here.

(UPDATE: Unfortunately, in the years since this was first written, the Genovese obit seems to have been purged from the NJO archives.)

Monday, March 05, 2007

Track Marks, Part Two

Following up on last week’s entry, here is the first installment of what I feel are some of the best – or at least most entertaining – DVD commentaries out there today, in rough alphabetical order. Comments welcome.

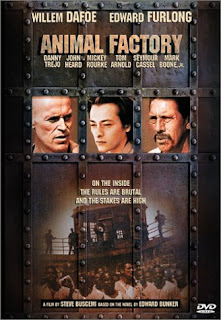

ANIMAL FACTORY (Columbia Tri-Star). Commentary by Danny Trejo and Eddie Bunker

Not many people saw this great Steve Buscemi-directed prison drama from 2000, though it sported a brutally authentic atmosphere and a terrific cast, including Willem Dafoe, Edward Furlong, Mickey Rourke, Seymour Cassell and the great Mark Boone Jr. The commentary adds yet another level of authenticity, coming as it does from ex-con-turned-novelist Eddie Bunker, who wrote the book it’s based on, and ex-con-turned-actor Danny Trejo, who co-stars and, with Bunker, co-produced. They were fellow convicts at San Quentin in the 1960s, and the commentary gives them a chance not only to reminisce about the day-to-day realities of prison life (“Some of the most politest people in the world are in the penitentiary,” Trejo says, “The last thing you want to do is be rude to another killer”), but also to marvel at where life took them afterward (“Boy, we come a long way, Bunk”).

Bunker, a career armed robber, sold his novel “No Beast So Fierce” to Hollywood while he was still in prison, and saw it made into the Dustin Hoffman movie STRAIGHT TIME. After his release, more novels (the best of them is 1981’s LITTLE BOY BLUE) and film roles (most notably Mr. Blue in RESERVOIR DOGS) followed. Trejo eventually became a drug counselor and served as a consultant on films such as RUNAWAY TRAIN and HEAT. He’s since become one of the busiest character actors in Hollywood, with roles in the SPY KIDS films, the new SHERRYBABY and the upcoming GRINDHOUSE. But their commentary here brings them back to another time, before Hollywood or anyone else came calling, and their futures promised only more of the same. Bunker died in 2005. His 2000 memoir, EDUCATION OF A FELON, is a classic.

Friday, March 02, 2007

And for those wondering ...

... what Dave does in his free time when he's not solving decades-old crimes or commenting on the weather, there's this from yesterday's New Orleans Times-Picayune:

N.O. BISHOP ORDAINED

At 43, Fabre is youngest in the nation

Thursday, March 01, 2007

By Bruce Nolan

A Baton Rouge parish priest became the youngest Catholic bishop in the country Wednesday in a two-hour ordination ceremony in which the Rev. Shelton Fabre was given a share of the leadership of the Archdiocese of New Orleans.

Fabre, carrying a crozier, or shepherd's staff, that once belonged to Archbishop Joseph Francis Rummel, walked around the packed interior of St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter absorbing applause from family, scores of New Orleans priests and about two dozen visiting bishops who participated in the ceremony.

Fabre assumes his office today, although he said in a recent interview that he, Hughes and Bishop Roger Morin have not yet decided how to divide the administrative duties of the archdiocese, which spans seven civil parishes surrounding New Orleans. Fabre will become pastor of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary Parish and will live there, although that parish's administrative duties will be handled by the Rev. David Robicheaux.

At 43, Fabre is the youngest Catholic bishop in the country and one of 10 active African-American bishops.

N.O. BISHOP ORDAINED

At 43, Fabre is youngest in the nation

Thursday, March 01, 2007

By Bruce Nolan

A Baton Rouge parish priest became the youngest Catholic bishop in the country Wednesday in a two-hour ordination ceremony in which the Rev. Shelton Fabre was given a share of the leadership of the Archdiocese of New Orleans.

Fabre, carrying a crozier, or shepherd's staff, that once belonged to Archbishop Joseph Francis Rummel, walked around the packed interior of St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter absorbing applause from family, scores of New Orleans priests and about two dozen visiting bishops who participated in the ceremony.

Fabre assumes his office today, although he said in a recent interview that he, Hughes and Bishop Roger Morin have not yet decided how to divide the administrative duties of the archdiocese, which spans seven civil parishes surrounding New Orleans. Fabre will become pastor of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary Parish and will live there, although that parish's administrative duties will be handled by the Rev. David Robicheaux.

At 43, Fabre is the youngest Catholic bishop in the country and one of 10 active African-American bishops.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)